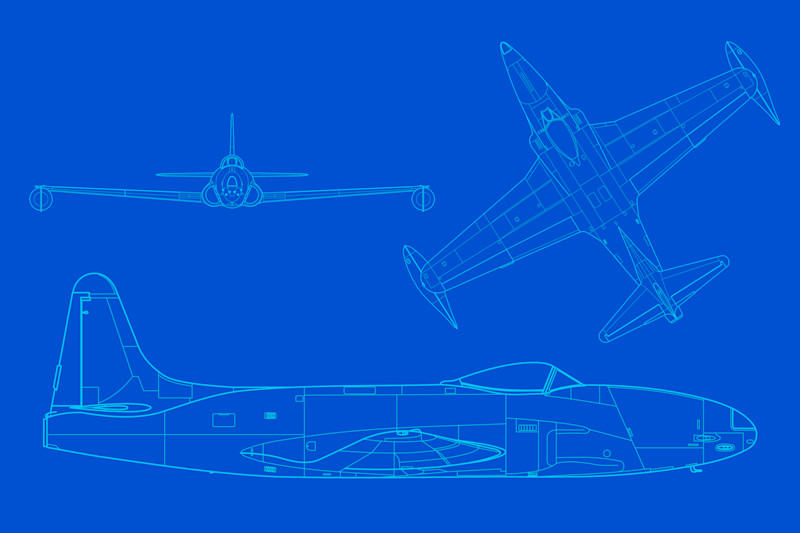

Back in 1943, Ben Rich and Kelly Johnson established what has become known as “Skunk Works” at what is now Lockheed Martin* to rapidly develop aircraft to fight in World War II. The team developed the P-80 Shooting Star, the first operational jet fighter used by the U.S. Air Force during the war, and it entered production just 143 days after the start of design.

Think of that. Under five months – design to production – for a mission-critical fighter aircraft. Something that absolutely had to work as intended.

To accomplish this history-making task, Johnson created 14 rules about getting things done. Among them are:

The Skunk Works manager has complete control of the program and reports to a division president or higher.

Restrict the number of people having any connection with the project: 10% to 25% of “normal” systems.

A very simple drawing and drawing release system with great flexibility for making changes must be provided.

Due to the small number of people involved, pay must be rewarded for good performance, not based on the number of personnel supervised.

This was all about creating an organization that allows people to do excellent work. It was designed to cut through both the inertia that is characteristic of too many projects and the organizational red tape that can inhibit that work.

Or as it is said today, it allows people to create “cool things.” But while the tools Johnson, Rich, and their Skunk Works colleagues could use to create cool things were limited, today’s tool box makes it easier – and even exciting. Additive, robots, digital twins … these and more leverage both the imaginations and capabilities of people in extraordinary ways.

So, what happens if the Skunk Works approach were combined with these new technologies?

This, I would argue, is already happening at a number of places that you haven’t heard of, as well as places that you have (like Tesla and Blue Origin).

As I’ve spent time in Silicon Valley lately, I’ve met young people who have established startups to develop innovative robotics, machining systems, and more. I’ve learned that they aren’t bound by “the way it has always been done” because for them, there isn’t an “always.” Low-cost sensors, automation, and other types of machinery allow them to create things that are digitally powered which can be used to create physical products that aren’t achievable by using these products in the “conventional” ways.

These are small companies – now – that may be absorbed into larger companies or cease to exist as the people behind them move on. The idea of limitations doesn’t necessarily occur to them.

And while small shops across the country have long created clever, innovative, and even cool things, these new facilities are taking things to a higher level.

Consider those four points from Kelly’s list: a small group that has the authority, control, and ability to make changes as needed – and is rewarded for its work. Leverage that with imagination and technology. The results can be incredible.

While you may think this is simply a case of small companies that will have limited impact, Tesla has upended the auto industry – and not just because of its electric propulsion system. It is taking entirely different approaches to its manufacturing processes, such as using giga castings that replace multiple stamped-and-welded components (and the attendant tolerance stack-ups). This is not new technology. But because traditional companies just didn’t do it that way, they haven’t. So, Tesla gets an advantage through tech.

The results of working in innovative ways with innovative tools are telling. According to a recent analysis by Reuters, Tesla’s net profit per vehicle is $9,574. It is $2,150 for GM and $762 for Ford.

Regardless of the industry, there is a need to attract new, younger talent. How this can be done is something that we at AMT work toward accomplishing, something that we have as a top-of-mind issue because it is vital. Tech and organization make the difference.

It occurs to me that the startups I met do things not incrementally but radically. They are interested in coming up with new, better ways of doing things. Their organizational structures are more aligned with Skunk Works than with a traditional, “this-is-how-we-do-it” operation. Their willingness to take on new manufacturing technologies is not inhibited by past practices. They want to do things that are cool. They want to make a difference.

And while that may seem idealistic, Tesla’s profits show it can also be financially successful. It works.

* Skunk Works still operates at Lockheed Martin, and the name is a registered trademark. On its website, the aerospace manufacturer describes it: “Just as Kelly intended, Skunk Works operates with a high degree of autonomy where employees are empowered to embrace the seemingly impossible tasks, tackle the toughest challenges and make a real difference for our customers.”